Caseload Alignment for Holistic Advising and Student Success

Student Success Supporting the Profession Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Student Affairs Partnering with Academic Affairs AVP or "Number Two" Faculty Graduate Mid-Level New Professional Senior Level VP for Student Affairs

February 4, 2026

In 2018 I joined NASPA to lead a grant-funded project with the explicit goal of supporting institutions’ ability to provide holistic advising to students. Over the last eight years, NASPA - Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education has created a national entity to support holistic advising redesign, and I am now proud to serve as our Assistant Vice President for Strategy and Partnerships leading the Advising Success Network (ASN) and working on research projects such as the 2025 Top Issues in Student Affairs Survey.

Advisors are often the people students interact with the most frequently on campus. They do more than transactional work during course registration-they are the front-line ambassadors of our institutions. They connect students to high-impact practices and provide coaching and mentorship to help them graduate on time. And the impact is measurable. An ASN-supported report from the Boston Consulting Group reveals a positive return on investment in advising staff, and support for holistic advising is clear in overall responses to the Top Issues survey this year. The majority of respondents indicate that increasing institution-wide collaboration to deliver coordinated student success services (65%) and increasing student access to personalized and academic advising (59%) are very important. However, one data point from the survey raised questions about how leaders are balancing these issues with growing demands on the time of advising professionals.The lowest-ranked item on the 2025 survey is, “Decreasing the caseload of academic and career advisors and coaches,” with 17% of respondents reporting it is not an important issue, and only 20% identifying it as very important.

NASPA’s ASN has supported hundreds of institutions through multi-year advising projects and every participating institution – regardless of size, location, mission, enrollment, and advising structure – prioritized clarifying advisor roles and responsibilities and ensuring advisor caseloads accommodate needs. Institutions typically land on this strategy because developing meaningful connections with students and providing them with proactive and individualized support is difficult in 15-minute interactions scheduled months apart. In fact, each year since 2021, advisors have cited high caseloads as the number one barrier to improving academic advising in Tyton Partner’s Driving Toward a Degree survey.

Given the variety of advising models, structures, and responsibilities across institutions, there is no universally agreed-upon caseload of students to advisors. Institutions we work with average 175 to 300 students per advisor, though specific populations like fully-online students may have dedicated advisors with smaller caseloads. UERU’s 2030 Boyer Commission Report recommends a ratio of 250 students per advisor at research universities, and Driving Toward a Degree 2025: Delivering Value and Ensuring Viability notes average caseloads of 286 students per advisor at public 4-year institutions and 319 students per advisor at public 2-year institutions.

As high-quality academic and career advising are essential to student success, I offer three possible explanations for why decreasing caseloads was de-prioritized by some Top Issues survey respondents:

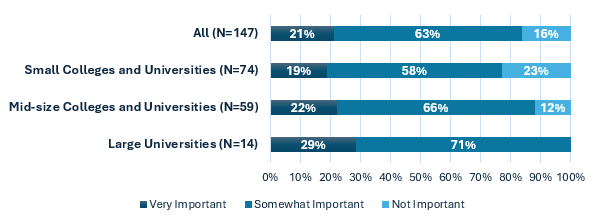

1. Small colleges and universities may deprioritize this issue if they have low advisor to student ratios. The survey included 147 responses to this question. Segmenting the data by institution size reveals differences in the importance for small, medium, and large institutions. Nineteen percent (19%) of respondents from small colleges and universities—those with fewer than 5,000 students—ranked the issue as very important to their institution whereas all respondents from large universities indicated the issue is at least somewhat important to their institution. Specifically, 9% of respondents from large universities ranked the issue as very important and the remaining 71% ranked the issue as somewhat important.

Even though this is the lowest-ranked issue, the overwhelming majority (84%) of professionals believe it is somewhat or very important. Given that caseloads tend to be higher at institutions with high enrollment, public institutions, and 2-year institutions, a low ranking could be correlated with lower overall enrollment at these institutions.

2. Respondents may believe this issue is important but seek more evidence and resources before investing in a strategy to lower caseloads. One respondent offered the notion that, “it would be nice,” to lower caseloads but budget challenges complicate the issue. If institutions are experiencing or anticipating stagnant or decreased budgets, they may believe this is an important issue but lack resources needed to hire more staff. As institutions navigate federal and state changes impacting local policies, many are sunsetting identity-based opportunities for student support. Faculty and staff with advising responsibilities are well-positioned and will likely be called on to provide additional psychological safety for students and take on even more responsibilities. Regardless of their level of resources, many institutions we have supported and awarded have adopted holistic advising models by adjusting faculty and staff roles and responsibilities and providing high-quality professional development opportunities as an advisor retention strategy.

3. Responses may illustrate a disconnect between strategic enrollment and student experience goals. Survey respondents serve as senior student affairs leaders and may be balancing a need to increase student enrollment with the implementation realities associated with increasing personalized student supports to serve those students upon arrival. To ensure a seamless student experience and enhance cross-campus collaboration, consider adding primary-role advisors to strategic planning conversations. They work closely with students and can serve as experts on which institutional policies may operate as unintended bottlenecks and barriers.

I am heartened that, while this was identified as the lowest priority issue, institutions are seeking ways to support advising staff. In open-ended responses, one institution shared that they are centralizing the coordination of advising across their colleges. A community college reported that they are re-evaluating advisor-to-student ratios and working toward decreasing caseloads while also developing an advising syllabus and implementing technology tools. Some reported that they are actively increasing the number of academic advisors and hiring student success coaches. While not every institution may have the resources necessary to follow these models, anyone can engage in peer learning by reviewing the free resources NASPA’s Advising Success Network has developed.

About the Author

Elise Newkirk-Kotfila is assistant vice president for strategy and partnerships at NASPA–Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education. She focuses on student success partnerships and leads the Advising Success Network. Prior to her work at NASPA, Elise worked as the director of applied learning for the State University of New York (SUNY), where she led SUNY’s 64 campuses through an applied learning initiative which culminated in providing at least one high-quality experiential learning opportunity to 460,000 students. Elise served for seven years as a board member for the Society for Experiential Education. She holds a master’s degree from the University at Albany where she studied Women’s Studies and Public Policy with a research concentration on community-university partnerships and a bachelor’s degree in Women’s Studies from The College of Saint Rose.

About the ASN

The Advising Success Network is a dynamic network of national organizations partnering to engage institutions in holistic advising redesign to advance success for all students, including Black, Latinx/a/o, Indigenous, Asian, and Pacific Islander students and poverty-affected students. The network develops services and resources to guide institutions in implementing evidence-based advising practices. Since its formation in 2018, ASN has supported over 267 institutions in 30 states and created more than50 open-source resources and free online professional development courses for advisors and students. ASN is coordinated by NASPA - Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education, and includes partners Achieving the Dream, the American Association of State Colleges and Universities, EDUCAUSE, NACADA: The Global Community for Academic Advising, the National Resource Center for the First-Year Experience and Students in Transition, the Center for Innovation in Postsecondary Education, and Young Invincibles.